TAPAS.network | 12 November 2025 | Commentary | David Knight

Vision-Led should be led by a vision – and here’s a way to build consensus on creating it

As discussion continues about approaches to creating more sustainable transport provision for new housing developments, suggests that careful thought is needed about ways of implementing the concept of objectives-led planning. In particular, he has successfully tested a methodology that can bring together different ways of looking at desired outcomes, and achieve Vision Statements that effectively reflect shared stakeholder values

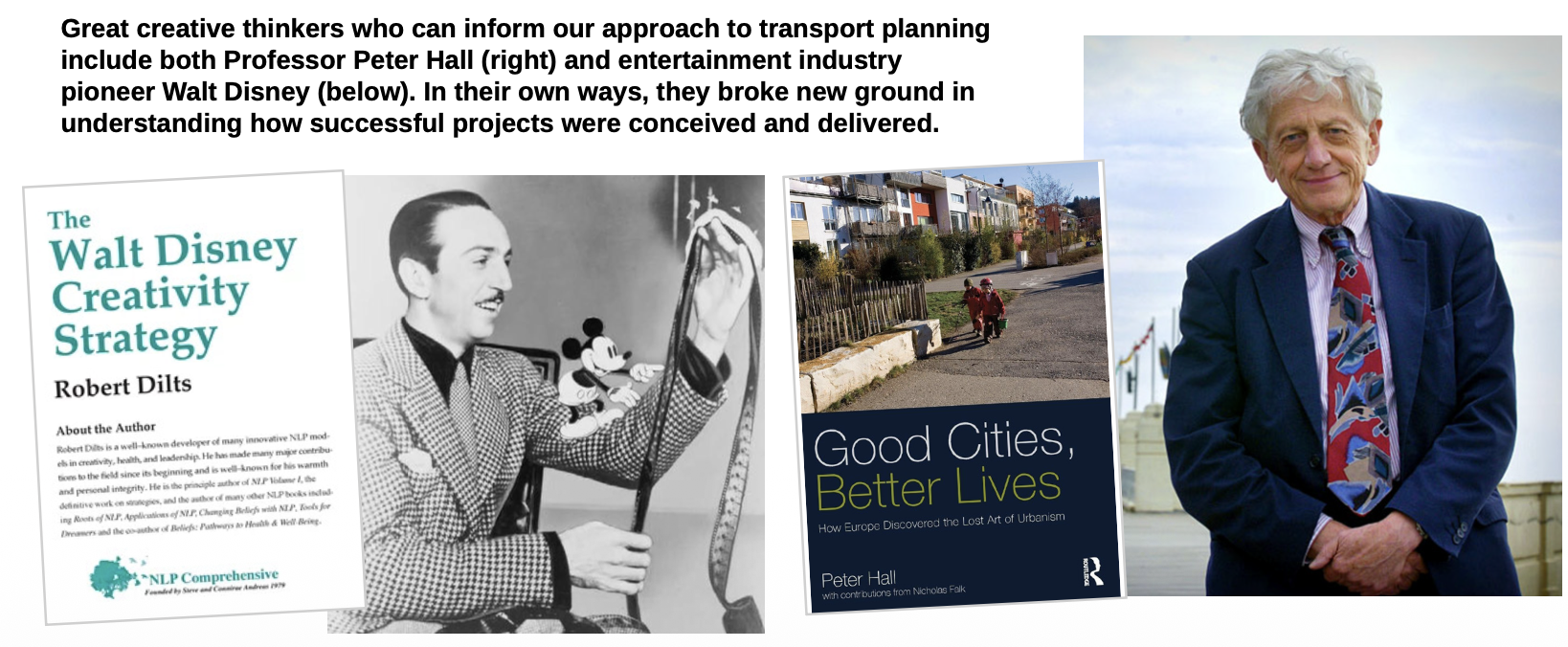

THE LATE SIR PETER HALL, in his book, Good Cities, Better Lives, published in 2013 just a year before his death, considered that the UK is no longer creating great urban spaces and had not done so for decades[1]. The much respected professor at the Bartlett School of Planning at University College London, was a key advisor to governments, whose work covered a wide range of topics, including transport, urban and regional planning, and the development of best practice concepts and thinking about how we can plan better.

In the book, Hall viewed Bath, Edinburgh, the Garden Cities and the post war new towns as in the great tradition, but that recent efforts at new communities have been “tawdry and superficial”. He would surely have joined in passionately the current debate about how to provide the Government’s promised 1.5 million new homes – especially the dozen or so new towns and urban extensions now being proposed – and the proper relationship of transport provision to that mission.

There is currently much discussion – including in recent LTT/TAPAS articles – about setting a vision of what these places should be, and it is encouraging that ‘Vision-led’ is now very much part of the transport planning vernacular, and may offer new hope of us addressing one of Professor Hall’s stated problem areas: “linking people and places through integrated land-use and transport planning.” Perhaps, surprisingly, in this article, I also consider how acknowledging the work of Walt Disney can help in this process.

As part of case study research for my recent PhD, A study of Transport Planning Practice in Large Scale Housing Developments in England, I sought to understand the nature of the vision for the permitted developments under construction that I was examining. What I found was that any form of vision appeared to be in the hands of the Developer and the Master Planner, and it was evident that there was actually a lack of a clear and meaningful identifiable vision amongst most of the schemes.

Typically the vision was generally unclear to the planning professionals I interviewed, and what was articulated was simply a basic understanding such as “a sustainable location for development” or even “a residential estate.” Perhaps the most telling response was from an experienced planning officer who said that it was the “later design code from reserved matters that gives the vision,” expressed as “high quality well connected urban extension which adopts a green infrastructure led approach and embraces sustainability at all levels to provide an exceptional place for people to live, work and play.”

Tellingly, he then summed this all up, “sounds like the sort of thing that is trotted out most times.” Not a great endorsement!

The vision was seen here as generic, but all was perhaps not entirely lost in my search, as a new town development I was researching had encouragingly developed a stated vision that was consulted on, and this included transport elements that were taken up and expanded upon in the Transport Assessment.

Further interviews on this scheme suggested that the vision had been held onto to some degree through planning and implementation, at least in part because it was clearly articulated and there was continuity of team members.

Are we now in a position to build further on that kind of approach? It may be the right time, as we now find ourselves in England with an updated National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) 2024[2] that overtly wants a ‘vision-led’ approach. Interestingly, ‘vision-led’ seems to be concerned with transport planning only, and perhaps not other disciplines as it might usefully be.

The updated National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) published last December by the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government that overtly wants a ‘vision-led’ approach

The NPPF definition is as follows:

Vision-led approach: an approach to transport planning based on setting outcomes for a development based on achieving well-designed, sustainable and popular places, and providing the transport solutions to deliver those outcomes as opposed to predicting future demand to provide capacity (often referred to as ‘predict and provide’). Annex 2: Glossary P.80.

The vision-led approach is about setting outcomes and is based on achieving a good design, and there is much policy and guidance to help us do this, to create a sustainable and popular place. What constitutes such a place is perhaps open to different views of what it would look like, depending on the consideration and extent given to different transport modes. Some clear visioning here would certainly be good.

Much of what the transport planning profession has identified as suitable for delivering projects that are vision-led concerns the use of ‘Decide and Provide’ or ‘Vision and Validate’ concepts, where scenarios of a future are adopted and then examined with a view to implementation. We thus design for the outcome we want, not accepting a continuation of the past just projected into the future, as was characterised by the old ‘Predict and Provide’ thinking.

NPPF paragraph 115 (d) identifies that

in assessing sites that may be allocated for development in plans, or specific applications for development, it should be ensured that: …. any significant impacts from the development on the transport network (in terms of capacity and congestion), or on highway safety, can be cost effectively mitigated to an acceptable degree through a vision-led approach.

The Vision-led approach here relies on ‘Decide and Provide’ methodology and assessment to deal with these impacts.

In practice, our recent experience of Decide and Provide on projects where different scenarios are assessed has resulted in more time, effort and cost being put into traffic analysis and modelling- which seems ironic when we should perhaps be increasing technical work on the provision of public transport and active travel. It seems evident to the writer that comparative scenario working needs to be manageable.

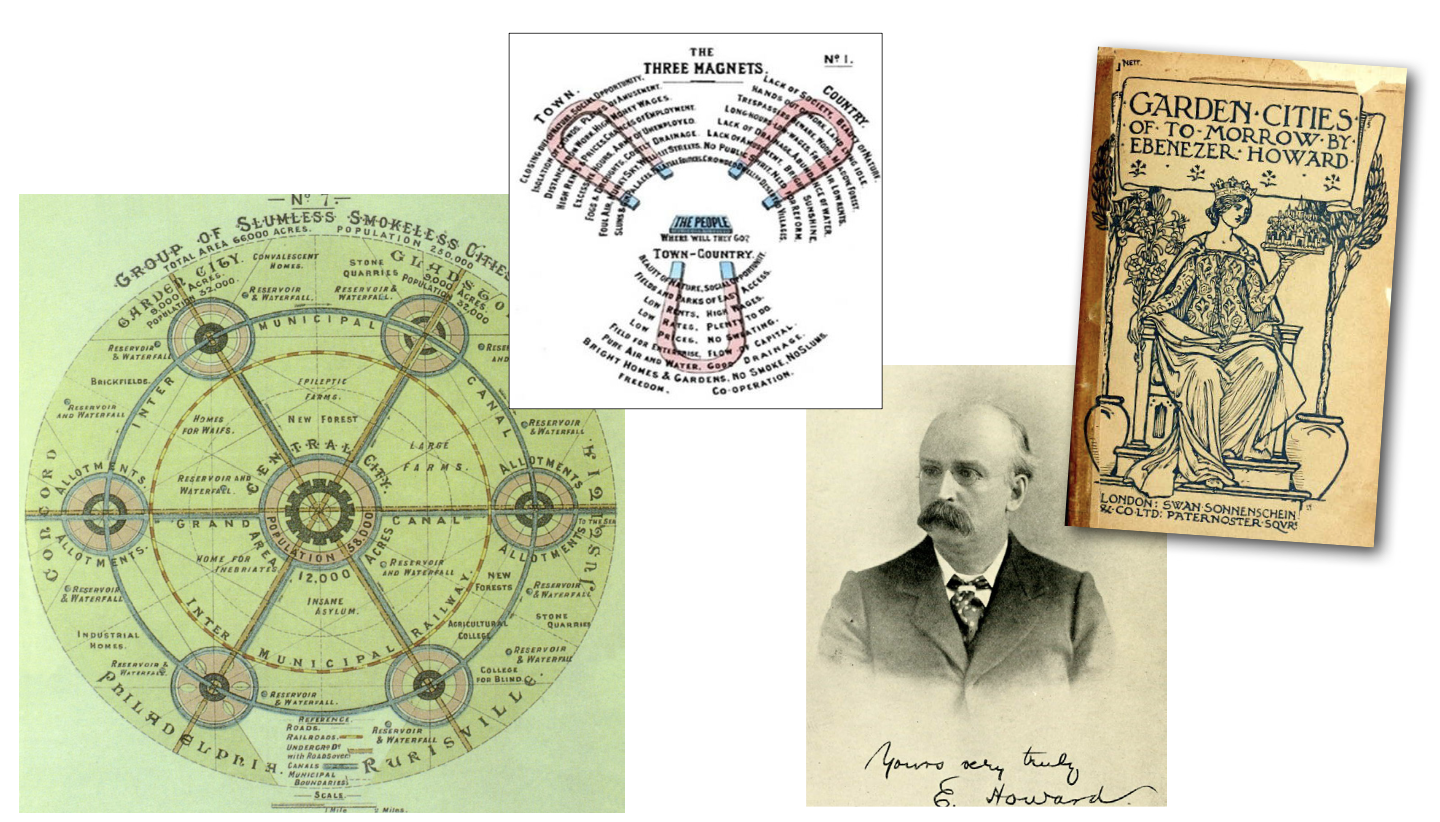

Ebenezer Howard’s New Town concept originally published in Garden Cities of tomorrow (pictured) reflected his thinking in the 1898 book Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. It was an urban planning model for a self- sufficient and contained community that combined the best aspects of both town and country living to address the social ills of industrial cities.

Core principles were his idea of the “Three Magnets” offering opportunity, amusement, and high wages of the town but also the benefits of the country providing beauty, fresh air, and low rents.

Those that have promoted this new thinking have brought some sense to the way we do things so we can move away from human forecasting (we cannot predict the future) which has always been an ‘Achilles heel’ of our method, as Professor David Banister puts it:

‘Decide and Provide’ (or ‘Vision and Validate’) as a methodology is bedding in, but I do not consider it to be the only important aspect here; for this to conceptually work well there is also the essential matter of the visioning itself. This means the method of creating a vision, even seeing ‘a vision of the future development,’ before we get into the detail of how we decide, and provide.

Defining a vision

To address this vital element, it is worth considering what it means to ‘have a vision’ and the Oxford English Dictionary definition is useful to us in this respect.

It is the ability to think about or plan the future with imagination or wisdom.

I would strongly argue that we do actually need both imagination and wisdom. It is our imagination that lets us form new ideas, images and concepts, as was beautifully illustrated by Sir Ebenezer Howard’s conception of the garden city3 (see images above). But the wisdom is where we bring our experience, knowledge and good judgement to bear to ensure that the vision can be delivered.

In our work at the consultancy Norman Rourke Pryme (NRP) we have been thinking about this for some time. We sought to introduce visioning to the transport planning of a large new community through a visioning workshop in 2023, where the key transport stakeholders came together in person to contribute to its conception and realisation.

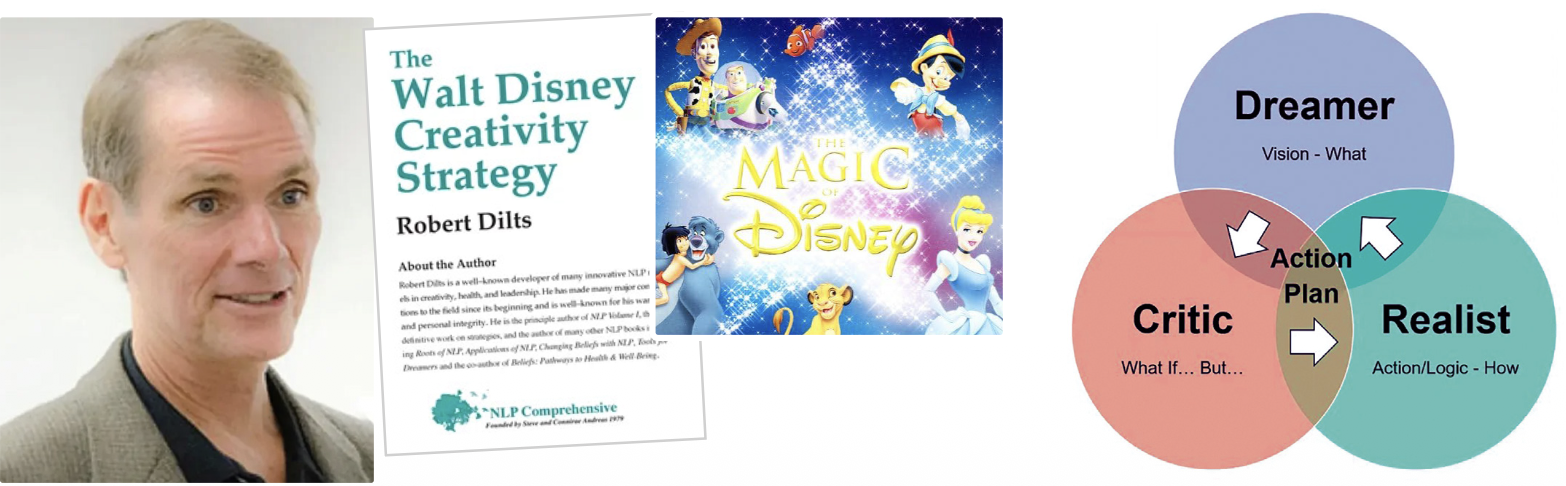

To support us in this endeavour we decided to use the ‘Three Perspective’ Disney method, developed by Robert Dilts (https://www.nlpu.com/Articles/article7.htm) based on Walt Disney’s approach (see below) and recommended to me by my mentor, Steve Rodd. This was the means to develop the vision and it proved successful. The facilitated workshop employed the method to allow all attendees to view the development and transport requirements from the three different perspectives of the Dreamer, the Realist and the Critic.

In this approach the production process starts with the dream, and develops through the other two lenses:

-

The Dreamer – creates a vision for the future. This can define what is wanted and the benefits of having it;

-

The Realist – gives ideas tangible and concrete timeframes, and assesses who can carry them out; and

-

The Critic – looks at what will work and what might go wrong, and acts as a filter.

It has been put to come together like this:

If you just dream – it is not enough

If you just criticise – you won’t have many friends

If you just act it out – you may end up without a direction

The dreamer, realist and critic positions allow the vision to be moulded. Our exercise thus allowed us to develop a Vision Statement, a set of objectives and a set of principles for the scheme, and each of these aspects is crucial. They overarched the Transport Assessment, and the ‘Decide and Provide’ scenarios to be tested.

In our workshop, which takes no more than half a day to conduct, the stakeholders take Dreamer, Realist and Critic roles in turn, individually writing down their thoughts in quiet, whilst some pointers are provided to each perspective. Between consideration of each there is an opportunity for individuals to give feedback to the facilitator.

Following the workshop, careful analysis takes place to pull the contributions together, and from this the vision statement, objectives and principles are drafted.

It is also important that one person writes the vision down for agreement, and that it is succinct - as vision statements prepared by committee can become wordy and meaningless. The expressed objectives and principles can be used to pick up more of the detail that is needed.

This first NRP visioning exercise was undertaken in advance of the publication of the latest version of the NPPF. Nonetheless it is considered that the approach is consistent with it, and can be used to explore what it means in the specific context for a scheme to be ‘well designed, sustainable and popular’ as now specified.

NPPF paragraph 109 meanwhile wants the vision-led approach deployed from the earliest stages of plan making, and sets out what this should involve: early engagement with local communities; ensuring transport considerations are integral to the scheme; addressing network impacts; realising transport infrastructure opportunities; pursuing public transport and active travel opportunities; and assessing environmental impacts. All of this can come into a visioning process, and fit well with the Disney Method approach as described, and that we have successfully adopted.

Robert Dilts (pictured), a pioneer in the psychological idea of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), documented Walt Disney’s creativity strategy, sometimes known as ‘the Magic of Disney,’ as a three-stage process involving distinct roles or thinking styles: the Dreamer, the Realist, and the Critic, deployed to effectively separate imagination, planning, and evaluation

We also need to recognise those people amongst the team and stakeholders who are able to set out a real vision of the place to be created, however incomplete this is, and support the best of their ideas. Within any group of people there will naturally be the dreamer, the realist and the critic. Some are even excellent at all three, and so all stakeholders should be invited to go through the production process and offer what they can. Everyone has a role in shaping the vision of the place, and how to get there.

It is important, of course, to remember that a transport vision will need to be part of a wider overall vision for the proposed development, or sit under this overall vision. This should involve collaboration with the wider development team, or at least see communication to ensure the transport vision is appropriate/consistent with the bigger picture.

There’s another important consideration to note too. NPPF paragraph 118 states:

All developments that will generate significant amounts of movement should be required to provide a travel plan, and the application should be supported by a vision-led transport statement or transport assessment so that the likely impacts of the proposal can be assessed and monitored.

How can you have such a vision-led transport statement or assessment without a properly generated and agreed vision? This approach now seems set and will become an important first stage of the Development Transport Planners’ work.

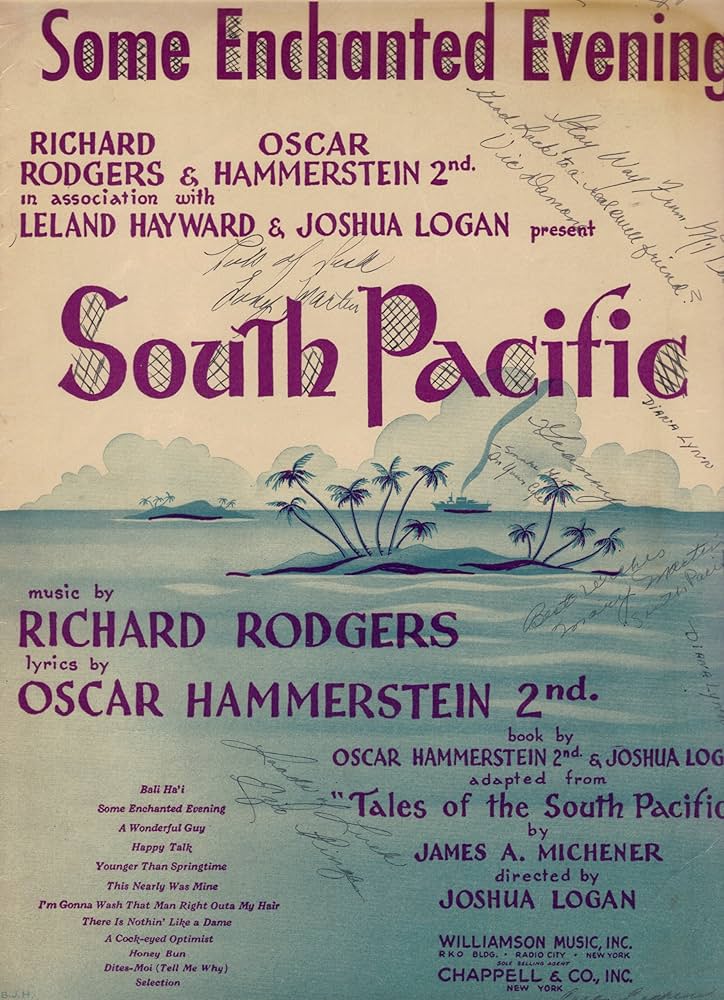

Let’s end our discussion with this familiar, and appropriate, refrain from the musical South Pacific:

Now that’s happy talk of creating a Vision-led approach that’s led by a genuine vision!

References and Links

-

Hall, P. (2014) Good Cities, Better Lives: How Europe Discovered the Lost Art of Urbanism. Abingdon: Routledge.

-

MHCLG (Ministry for Housing. Communities and Local Government), 2024. National Planning Policy Framework. MHCLG, London.

-

Howard, E (1902), Garden Cities of To-morrow (2nd ed.), London: S. Sonnenschein & Co, pp. 2–7.

Dr David Knight has over 35 years experience in Transport Planning, which he heads at consultant NRP, leading work on large-scale housing developments in the south of England. These have been a focus for his PhD at Loughborough University. He seeks to support better relationships across the industry, and runs and contributes to professional training courses, particularly promoting work on transport visioning, active travel led development, and mobility hubs. He has researched frameworks and tools to evolve the Transport Assessment process.

This article was first published in LTT magazine, LTT926, 12 November 2025.

You are currently viewing this page as TAPAS Taster user.

To read and make comments on this article you need to register for free as TAPAS Select user and log in.

Log in